Natural Magick (1658)

What is your favourite book in this library? I have the privilege of being able to spend more time browsing through the shelves than most others who have been asked this question but this has not made the task any easier. Frequently I will open a book and be surprised by what I'm holding. On my very first day, for instance, I discovered the library's first edition of The Four Books of Architecture by Palladio (1570), with its exquisite woodcut illustrations. The day after, whilst neatening a shelf, I stumbled across a 1553 copy of Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia.

Whilst there is an undeniable optical and haptic pleasure to be found in handling a four hundred year old tome bound in tooled calf leather, the old adage that a book should never be judged by its cover holds true. One seemingly unremarkable work bound in battered and stained vellum may contain a treatise that was world-shatteringly revolutionary in its day, such as the library's 1638 copy of Galileo's Discorsi E Dimostrazioni Matematiche. On the shelf behind my left shoulder as I write, somewhat foxed and bound in drab marbled card, is Descriptions of an Electrical Telegraph and of some other Electrical Apparatus by Francis Ronalds (1823). Next to this is an equally ordinary looking 1856 tract on electrical telegraphy by William Fothergill Cooke. Taken together they are two of the key works by the pioneers who developed and implemented the world's first viable electric telegraph systems – who therefore began the process of wiring together the world with extensive telecommunications infrastructure, which fundamentally changed the human experience of time, space and information. Other tomes turn out to be much older and far less straight-laced than their rebound 19th century forms might initially suggest. This is the case for what I will call one of my favourite discoveries in the Iron Library so far.

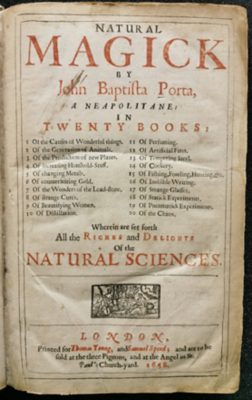

Magia Naturalis by Giambattista della Porta was first published in Naples in 1558. Within the first ten years, it had been translated into Italian, French and Dutch, and the original Latin text went through five editions. The Iron Library's copy is a first edition of the English translation, Natural Magick, which was published one hundred years later in London by Thomas Young and Samuel Speed in 1658.

Giambattista della Porta is an unusual figure to say the least. The son of a Neapolitan nobleman, he was raised surrounded by scholars and musicians under strict tutelage guidelines set by his father, which perhaps explains how he and his brothers became such distinguished polymaths. He seems to have thrived on a mystique that bordered on the heretical and was at one point interrogated by the Inquisition. Indeed, he was derided as a sorcerer and conjurer, as he himself reports in the preface (page 3.) as part of a rather bile-laden tract defending his work and attacking those who had criticized him since the book's first edition. In addition to his scientific work, he also wrote several plays, and is regarded as one of the great cryptographers of the renaissance.

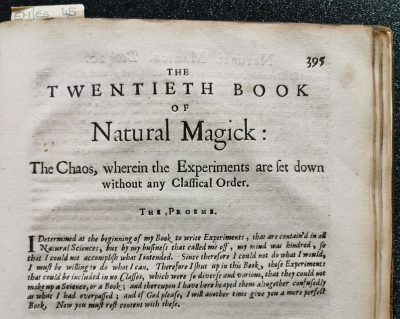

To the modern eye, Natural Magick is a curious jumble of subjects, for which the title of Book 20, 'The Chaos, wherein the Experiments are set down without any Classical Order', could well describe the whole tome! Yet for Della Porta, the meandering way through the chapters seemed an entirely logical manner of setting out its ideas, the result both of his own work and of others, such as Pliny. Its raison d’être in the collection of the Iron Library is likely Book 13, 'Of Tempering Steel', which Della Porta places between a book on artificial fires and another containing his recommendations on cookery. Of the other topics covered after the opening speculations on the binding laws of the universe, animal husbandry, the grafting of fruit trees, the preservation of fruit, and experiments with wind instruments for meteorological research, stand out as the most practical and sensible, they having an economic relevance for many potential readers at that time. In amongst these, however, can be found advice – for instance – on how to make various animals, including elephants, drunk (p.334)!

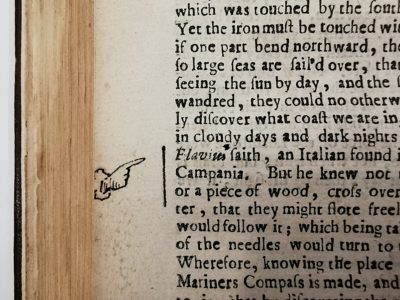

As an object, the Iron Library's copy has several features of note. A previous owner seems to have taken particular interest in the subject of magnetism and the identification of North, and annotated two chapters with manicules (pointing finger marginalia) (p.206-7). Page 226, meanwhile, is noticeably the most heavily stained of any in the book, with some residues caked over passages of Chapter IX of Book 8 'Of Physical Experiments'. These passages include recipes against poisons and cures for the plague, the latter of which struck London seven years after the book's publication there. One can only wonder whether this damage to the book might not have been the result of some desperate search for an antidote.

It is a difficult work to categorise. In light of its publication history and author's intent to bring the natural sciences into a language and context that could be more generally understood and applied, there is a fair case for describing Natural Magick as one of the earliest examples of pop science, albeit a sort of pre-Baconian pop science meets self-help guide. Therefore, in spite of what could be politely termed its more peculiar recommendations, its publication marks something of a watershed moment in the history of science communication.